Winnie The Pooh In Russia

My wife went to the Soviet Union six weeks before the military coup in 1991. While she was there, she bought a lot of books to bring back with her to the U.S. I discovered this one for myself recently while we were going through our bookshelves to thin out our stock. For some reason, for me Piglet was the first giveaway that these are characters from A.A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh.

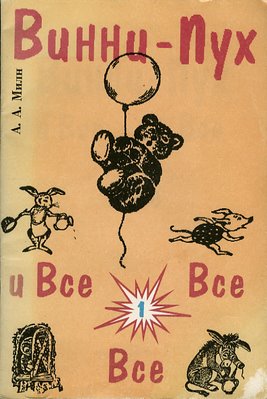

My wife went to the Soviet Union six weeks before the military coup in 1991. While she was there, she bought a lot of books to bring back with her to the U.S. I discovered this one for myself recently while we were going through our bookshelves to thin out our stock. For some reason, for me Piglet was the first giveaway that these are characters from A.A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh.The book is more of a booklet, 8 1/2 x 11" sheets that are folded and saddle-stitched (stapled). The paper is Bible-thin and the print quality is poor. The book's single spot color is brown, and all the pictures are brown, and look like they were generated on some sort of early computer or just run through one in the printing process. But they reflect a very different view of Winnie the Pooh than the one we are so familiar with in the United States. Looking at it - especially when being unable to read a word of it - is an interesting study in how visuals can come to seem embedded within the words, and how works of imagination can be taken over, wholly consumed, and stuffed and mounted by their copyright holders.

Potentiality and Actuality

The accretion that is Winnie the Pooh, built in my lifetime and just before it by Disney, wore out his welcome in my life long ago. For the past ten years or so he has stood simply as a logo for moms in sweats who wear the mark as a kind of visual cipher signifying Gemütlichkeit in the same way that Mickey Mouse apparel signifies Gemeinschaft.

If we rephrase the Wikipedia entries for these two Germanic terms, we could produce our own lexicon of Disney wear:

Mickey-wearers are broadly characterized by a moderate division of labor, strong personal relationships, strong families, and relatively simple social institutions. In such societies there is seldom a need to enforce social control externally, due to a collective sense of loyalty individuals feel for society. Historically, Mickey-wearing societies were racially and ethnically homogeneous.(Adapated from the Wikipedia entry for Gemeinschaft)

The underlying concept of Winnie-the-Pooh-cladding is that social tensions and certain environments can cause stress, resulting in a feeling of alienation. Winnie-the-Poohism is an active way of preventing such negative influences by going to places and/or meeting with people that are regarded to be Winnie-the-Pooh-ish. A Winnie-the-Pooher is one who takes part in this lifestyle and knows about the tensions he/she is able to cause, and thus tries to avoid these things actively. This way an agreement is established to make an "environmentally cosy" site (Heuriger, garden, cellar, backyard restaurant, living room...) "socially cosy." One characteristic of a Winnie-the-Pooh situation is that one could blind out everything else (past, future, other places and absent people) and yet everything would be fine (an eternal "now and here"). Winnie-the-Poohists describe that as "leaving everything at the doorstep" (though a Pooh-ish place doesn't necessarily have to be inside a house). (Adapated from the Wikipedia entry for Gemütlichkeit)

Even E.H. Shepard's illustrations from the original Milne feel refreshing after a lifetime of Disney.

The Russian edition I've been browsing lately is now helping me reimagine Pooh even further, and got me wondering about how such characters become fixed in our minds in a certain style, and what it takes to break them out of that form and regain our perception of something more abstract which might truly interest us.

The Russian edition I've been browsing lately is now helping me reimagine Pooh even further, and got me wondering about how such characters become fixed in our minds in a certain style, and what it takes to break them out of that form and regain our perception of something more abstract which might truly interest us.At left, Pooh is falling from the tree in the first chapter of the book, after using a balloon to attempt to get at their honey. This is also the first chapter of the English-language version of the book.

In the 1930s the image of Pooh was a fairly fluid thing. A variety of illustrators in the U.S. took a crack at him when the stories were serially published there, and although the subsequent book editions had been given a strong imprint by illustrator E.H. Shepard (the illustrations you will undoubtedly see today), Milne welcomed Pooh's exportation to children's theatre, sound recording of Pooh stories by Jimmy Stewart and Gene Kelly, in "early animated paper films" (Wikipedia's wording - I'd certainly like to see those!) and in adertising various goods and services.

Neither Milne nor Shepard considered these characters to be their legacy. Both were leading contributors to the political magazine Punch and felt their most significant work was done there. Shepard reportedly grew to "hate" Pooh, and Milne wished to be remembered as a playwright rather than as the author of "four trifles for the young."

This may help explain why Milne left the rights to Winnie the Pooh to four different groups, who became quite confused over how to best carve up this golden-egg-laying goose. Disney bought rights from one of those groups and has more or less won the slugfest over who can legally employ the characters.

Death and Rebirth

Here, in the second story in the book, Rabbit entertains Pooh in his home prior to Pooh getting stuck in Rabbit's hole on the way out. In the Disney version of the stories all of the characters are heavily caricatured versions of those in the book, and the mean-spirited Rabbit takes to drawing on Pooh's rear end, if I remember correctly. In fact, this is one of the few Pooh stories (along with the bees and the balloon) used by Disney in the company's cartoons and videos.

Here, in the second story in the book, Rabbit entertains Pooh in his home prior to Pooh getting stuck in Rabbit's hole on the way out. In the Disney version of the stories all of the characters are heavily caricatured versions of those in the book, and the mean-spirited Rabbit takes to drawing on Pooh's rear end, if I remember correctly. In fact, this is one of the few Pooh stories (along with the bees and the balloon) used by Disney in the company's cartoons and videos.The rest of the stories the Russian editor used appear to come from The House at Pooh Corner, Milne's second book of Pooh stories, which introduces Tigger (who became a leading character in Disney's cast) and which ends with Christopher Robin leaving Hundred Acre Wood forever, too old to play in the forest with stuffed animals. It's the perfect culmination to what is effectively an exercise in nostalgia. I mentioned earlier that parental influence helps suppress bad children's characters, but it also props up others artificially, like a welfare state's subsidized television stations might take the peaks and valleys out of a free market of popular expression. If you have any doubts about the role parents play in keeping children's books alive, you need only look to the persistence of nostalgia - a concept that is completely irrelevant to young children - as one of only a handful of the most influential themes in the history of children's literature. Sometimes this powerful source of inspiration, spoken by and largely to adults, is transformed into something of real, authentic relevance to young children. Sometimes it isn't. In the case of A. A. Milne's Winnie the Pooh, I can come down on either side of this question depending on my mood.

The things which tend to push me towards a hatred of Pooh are the things that Disney has done to him. I am a friend of Gemütlichkeit and the idyll of comfort, love, and total understanding that it promises. Such moments and experiences do exist, and they can be among the most important experiences of our lives. But when such things are turned into commodities, things always get ugly. At left we have the most extreme caricature Disney has come up with, from the live-action children's show The House At Pooh Corner, which I remember watching with my little sister back in the 1980s. Back then, I was just bored. Now, I see things, tragic things, in Pooh's face. The pinched, pained face of Pooh in this show reminds me of the freakish, post-plastic surgery Catherine O'Hara in For Your Consideration. The weathering of Pooh's visage - the theatrical revues of the 1930s, the shared inheritance of rights among multiple, entrepreneurial parties, the sellouts to Disney, the lawsuits - these have all been washed away, leaving a horrific hybrid between product and product packaging. This expression, this grimace - it is a death mask. This is the face of a character trapped in a kind of living death. He is a frozen image, begging for release.

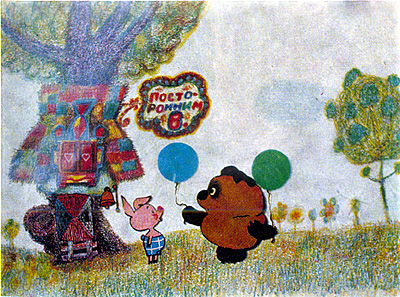

The things which tend to push me towards a hatred of Pooh are the things that Disney has done to him. I am a friend of Gemütlichkeit and the idyll of comfort, love, and total understanding that it promises. Such moments and experiences do exist, and they can be among the most important experiences of our lives. But when such things are turned into commodities, things always get ugly. At left we have the most extreme caricature Disney has come up with, from the live-action children's show The House At Pooh Corner, which I remember watching with my little sister back in the 1980s. Back then, I was just bored. Now, I see things, tragic things, in Pooh's face. The pinched, pained face of Pooh in this show reminds me of the freakish, post-plastic surgery Catherine O'Hara in For Your Consideration. The weathering of Pooh's visage - the theatrical revues of the 1930s, the shared inheritance of rights among multiple, entrepreneurial parties, the sellouts to Disney, the lawsuits - these have all been washed away, leaving a horrific hybrid between product and product packaging. This expression, this grimace - it is a death mask. This is the face of a character trapped in a kind of living death. He is a frozen image, begging for release. Winnie the Pooh has been quite popular in Russia. And unlike in the United States, no one exclusively owned the right to draw him. Above, Winnie the Pooh nesting dolls. Below, one of the popular Winnie the Pooh cartoons from Soviet animation powerhouse Soyuzmultfilm.

Winnie the Pooh has been quite popular in Russia. And unlike in the United States, no one exclusively owned the right to draw him. Above, Winnie the Pooh nesting dolls. Below, one of the popular Winnie the Pooh cartoons from Soviet animation powerhouse Soyuzmultfilm. But still, the Disney image remains. I can see these other figures while I look at them - examine them, even attempt to refresh my image of who Pooh might be by using them, following their lines, absorbing their colors. But when I turn away, this remains.

But still, the Disney image remains. I can see these other figures while I look at them - examine them, even attempt to refresh my image of who Pooh might be by using them, following their lines, absorbing their colors. But when I turn away, this remains.

Characters can't always be brought back from the brink. Sometimes they should just be allowed to die. And when market forces prevent this from occurring - when there is still money to be made from the mask, from the shell of the creature that animates the books - the words, which bear no responsibility for the evolved image, suffer anyway. And we read, and try to forget.

1 comment:

Great essay! And delightful Soviet cartoon at the end.

Post a Comment