The Magic Pudding And The Great War

My brother recently sent me a copy of the fantastic and inimitable children's story The Magic Pudding, written by Norman Lindsay and published in 1918. At nearly forty, the artist and author had already made a name for himself with his controversial artwork (he became a devotee of Nietzsche's moral philosophy as well as embracing his neo-Classicism) and had scandalized audiences in his native Australia and abroad with works like his 1912 "Crucified Venus." The pen-and-ink drawing depicts a nude woman in a Venus de Miloesque pose being nailed to a cross by Catholic friars while Puritans, priests, and preachers look on, and showcases his marriage of a realist style from the 19th century with a strong desire to criticize conventional social mores. (You can see that as well as more of his drawings, paintings and etchings here.)

My brother recently sent me a copy of the fantastic and inimitable children's story The Magic Pudding, written by Norman Lindsay and published in 1918. At nearly forty, the artist and author had already made a name for himself with his controversial artwork (he became a devotee of Nietzsche's moral philosophy as well as embracing his neo-Classicism) and had scandalized audiences in his native Australia and abroad with works like his 1912 "Crucified Venus." The pen-and-ink drawing depicts a nude woman in a Venus de Miloesque pose being nailed to a cross by Catholic friars while Puritans, priests, and preachers look on, and showcases his marriage of a realist style from the 19th century with a strong desire to criticize conventional social mores. (You can see that as well as more of his drawings, paintings and etchings here.)

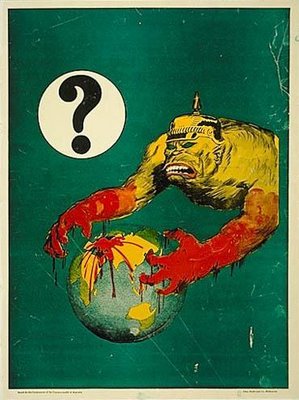

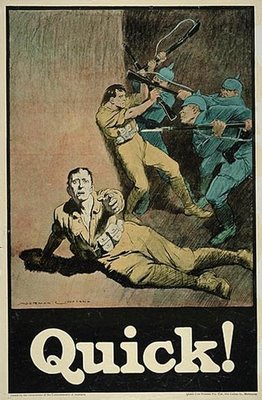

That combination would have made him a fitting companion for the Italian Dionysian and political dynamo Gabriele D'Annunzio, fifteen years his senior and half a world away. The term many such men favored - "vitalist" - speaks to the hypermasculinity (scenes of rape were popular "classical" subjects) that was the antithesis of those other libertines, the Bohemians (not to be confused with people from Bohemia). Lindsay illustrated Petronius and Casanova, and like D'Annunzio blended politics and art fluently, following that strange path of libertines turned nationalists, whose calcified views in that period saw heroic "supermen" as the champions of exalted appetites rather than as the Puritans they proved themselves to be. Drawing on his years as a political cartoonist, Lindsay first showed the strength of his poison pen with a portrayal of World War I-era Germany that would have been at home in a Gothic (or graphic) novel. Lindsay did for the German menace in 1918 what Frank Miller would do for urban street gangs in his seminal 1986 Batman-redefining graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns; both preyed on dark, primal fears by drawing nightmarish references into Technicolor reality to approach an anxiety-inducing threat: Australia's position in World War I was markedly different from that of the U.S. As a part of the British Commonwealth, Australia was saddled with both immediate participation in the war and the lack of an existing army beyond what England believed Australia needed for her self-defense, so there was immense pressure to raise a standing army from scratch. With the help of a massive propaganda campaign the Australian government raised an army of 20,000 men in less than four months, and kept the bodies coming for four years. Lindsay had learned in 1917 that his brother had been killed in the war, and took part in Australia's final recruiting drive the following year, producing several recruitment posters that worked hard to stir up patriotic guilt among young Australian men.

Australia's position in World War I was markedly different from that of the U.S. As a part of the British Commonwealth, Australia was saddled with both immediate participation in the war and the lack of an existing army beyond what England believed Australia needed for her self-defense, so there was immense pressure to raise a standing army from scratch. With the help of a massive propaganda campaign the Australian government raised an army of 20,000 men in less than four months, and kept the bodies coming for four years. Lindsay had learned in 1917 that his brother had been killed in the war, and took part in Australia's final recruiting drive the following year, producing several recruitment posters that worked hard to stir up patriotic guilt among young Australian men. Tensions were high in the recruiting of Australian troops. Referenda to allow for conscription were twice put before the Australian people and defeated both times, while the government used techniques of harrassment, censorship, and arrests of prominent opponents of the war to put as much pressure as possible on a generation of Australian men. The strongest voices of opposition were often the labor organizations, who feared that Australian workers would be replaced by cheap foreign labor which would undercut wages, as well as being motivated by a pacifistic opposition to the war consistent with international workers' movements.

Tensions were high in the recruiting of Australian troops. Referenda to allow for conscription were twice put before the Australian people and defeated both times, while the government used techniques of harrassment, censorship, and arrests of prominent opponents of the war to put as much pressure as possible on a generation of Australian men. The strongest voices of opposition were often the labor organizations, who feared that Australian workers would be replaced by cheap foreign labor which would undercut wages, as well as being motivated by a pacifistic opposition to the war consistent with international workers' movements.

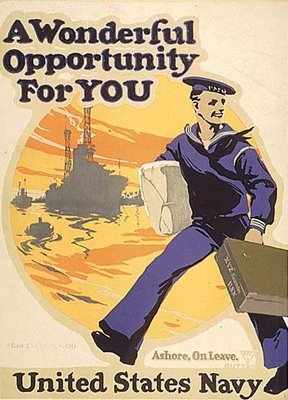

The U.S. has rarely produced such blatant appeals to young men to back up endangered fellow soldiers, and in World War I there was certainly much less at stake. The U.S. did not enter the war until 1918 and then confronted the heavily-reported horrors of the Great War with recruitment posters like this one: In World War II there was no need of U.S. recruitment posters, except to smoke out the few able-bodied men who did not immediately enlist, and the vast majority of wartime propaganda dealt with issues of conservation, production, and secrecy. In the only official "wars" of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the U.S. government has stuck with the theme of personal benefit in its recruiting efforts (college education, work experience, adventure, development of character) and never dared to play to young Americans' guilt in attempts to draw recruits. The closest U.S. recruitment efforts have come comes in its recently unveiled new recruitment campaign, which participates in a broader cultural commendation of the army unit as a collective source of spiritual value for its members independent of the particular work they happen to be doing.

In World War II there was no need of U.S. recruitment posters, except to smoke out the few able-bodied men who did not immediately enlist, and the vast majority of wartime propaganda dealt with issues of conservation, production, and secrecy. In the only official "wars" of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the U.S. government has stuck with the theme of personal benefit in its recruiting efforts (college education, work experience, adventure, development of character) and never dared to play to young Americans' guilt in attempts to draw recruits. The closest U.S. recruitment efforts have come comes in its recently unveiled new recruitment campaign, which participates in a broader cultural commendation of the army unit as a collective source of spiritual value for its members independent of the particular work they happen to be doing.

Unfortunately, Lindsay's devotion to Nietzsche and to heroic politics carried him fully down the path of anti-Semitism and broader Anglo racism. That, as well as his lifelong war against Modernism in art, had more to do with his current status as a minor footnote in the history of art than his Australian provenance, for he was truly an international figure in his day.

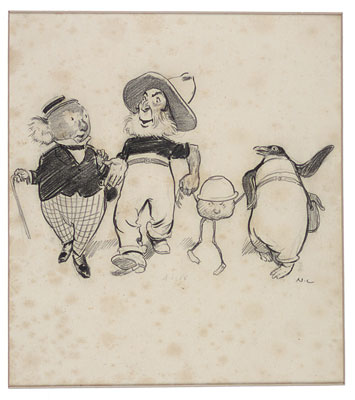

Against all that we must weigh The Magic Pudding, a wonderful, boisterous, lyrical work of fiction which is quite possibly the funniest children's book ever written. From its initial conceit - a walking, talking bowl of steak-and-kidney pudding which is not only "bottomless" but demands to be consumed, and prods its owners into brisk exercise when they are full, that they might eat again sooner - Lindsay tells the going-nowhere-fast story of a koala bear, a penguin, and a sailor who struggle to protect their prized possession from a pair of "Puddin' Thieves," complete with violent brawls, sea chantys, mock oratory and obfuscating legal proceedings, and illustrated throughout in the truly delicious style of an expert caricaturist.

It is easy to opine that Lindsay used The Magic Pudding as a means of escaping from the intense seriousness and tragedy of the war that consumed Europe and, by extension, his home country of Australia. It is also probably true. But it is equally likely that the sentiments of The Magic Pudding are entirely consistent with Lindsay's other work and with an eccentric's self-made philosophy, applied towards children, which insisted that the world is yours for the taking, that the worst in life is full of humor, and that pomposity seeks to oppress the free spirit everywhere. The book depicts a world in which even the greatest flights of fancy are permeated by perpetual conflict - a world Lindsay could depict in a cathartic way, but also one that he could only do justice to in the form of a freewheeling comic parable.

Some have cited the story's creation as Lindsay's follow-up to an argument he had with a friend, who observed that children preferred above all to read books about fairies. Lindsay countered, the story goes, that what children really loved to read about was food.

A more detailed assessment of Lindsay's life and work can be found here.

No comments:

Post a Comment