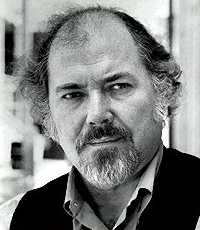

Desire, Death and Robert Altman

This post welcomes guest contributor Joshua Gibson, whose own blog, Fagistan, features great criticism of literature, film, photography, and pop culture. If child-prodigy painter Akiane proves to be a spiritual fraud, you will have heard it on Joshua's blog first. Links: Gibson's Blogger profile | his blog

________________________________________________ Robert Altman, whose death on Monday night has left a raw wound in American cinema, had a career that is impossible to summarize. The obituaries take a brave stab, but the lists of hits (MASH, Short Cuts) and bombs (Popeye, Dr. T and the Women) are the least interesting thing about one of the most startling voices in film.

Robert Altman, whose death on Monday night has left a raw wound in American cinema, had a career that is impossible to summarize. The obituaries take a brave stab, but the lists of hits (MASH, Short Cuts) and bombs (Popeye, Dr. T and the Women) are the least interesting thing about one of the most startling voices in film.

As little interest as I have in merely listing Altman's achievements and failures (you can see the Internet Movie Database for a full filmography, or get some context here), even less do I have in writing about Nashville or The Player, films that have been, and will be, discussed for years. Rather, I'd like to take a few moments to celebrate a film in which Altman's art, sinister and beautiful, was at its mystical and aesthetic peak. By the time he made 3 Women in 1977, Altman had already made four masterpieces. These films deconstructed and illuminated everything from the war movie to the Western to the noir gumshoe. 3 Women can be seen, then, as Altman turning his eye toward horror. But to me it is also the supreme embodiment of the narratives that flow from his aesthetic sensibility. Many great directors allow aesthetics to swallow narrative whole (Cocteau, Tarkovsky) and many others fashion an aesthetic to fit their narrative desires (Bergman, Kurosawa) but rarely does a filmmaker's aesthetic sense produce the narratives to support and reflect it. Admittedly, as soon as I write such a sentence, a dozen examples come to mind (Eisenstein, Renoir, et cetera) but Altman deserves such exalted company.

By the time he made 3 Women in 1977, Altman had already made four masterpieces. These films deconstructed and illuminated everything from the war movie to the Western to the noir gumshoe. 3 Women can be seen, then, as Altman turning his eye toward horror. But to me it is also the supreme embodiment of the narratives that flow from his aesthetic sensibility. Many great directors allow aesthetics to swallow narrative whole (Cocteau, Tarkovsky) and many others fashion an aesthetic to fit their narrative desires (Bergman, Kurosawa) but rarely does a filmmaker's aesthetic sense produce the narratives to support and reflect it. Admittedly, as soon as I write such a sentence, a dozen examples come to mind (Eisenstein, Renoir, et cetera) but Altman deserves such exalted company.

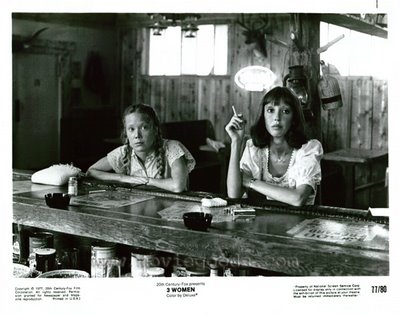

3 Women tells the story of a shy, naive young girl (Sissy Spacek) who falls into a bizarre friendship with her seemingly wiser co-worker and roommate (Shelley Duvall.) As so often before and after, Altman shows their lives in a series of partially realized scenes, snippets of lives we can never fully grasp. Even as the camera lingers, lovingly and threateningly, on their faces, the lens never penetrates beneath their glassy eyes. And here it is, the profound insight of Altman's work: cinema can never do more than gaze. The voyeur's dream of slipping into another's life, of understanding her desires and fantasies, can never be realized on screen. And so, Altman lets us gaze. He lets us gaze upon Duvall's insipid flirtations with men who laugh behind her back, and upon Spacek's frightened and frightening games of deception. Slowly, Spacek's slippery grasp on sanity loosens and Duvall finds herself, once the object of desire and lust, cast aside as Spacek's character dies and is reborn as... Duvall. And here, the narrative proves Altman's point. Spacek changes her name and her behavior, transforms herself into the woman she believes Duvall is. But what emerges is a grotesque caricature of womanhood and strength, mocking Duvall's essential innocence with lustiness and vulgarity. In trying to take Duvall's place, Spacek succeeds only in unleashing her own hungry ghost.

And so, Altman lets us gaze. He lets us gaze upon Duvall's insipid flirtations with men who laugh behind her back, and upon Spacek's frightened and frightening games of deception. Slowly, Spacek's slippery grasp on sanity loosens and Duvall finds herself, once the object of desire and lust, cast aside as Spacek's character dies and is reborn as... Duvall. And here, the narrative proves Altman's point. Spacek changes her name and her behavior, transforms herself into the woman she believes Duvall is. But what emerges is a grotesque caricature of womanhood and strength, mocking Duvall's essential innocence with lustiness and vulgarity. In trying to take Duvall's place, Spacek succeeds only in unleashing her own hungry ghost.

And all through the film wind the visual manifestations of this ghost in the form of murals painted by the third woman of the title, a silent crone who paints looping serpents that gaze up from the depths of a swimming pool, silent but hungry, unknowable but full of desire. These serpents are Spacek and they are Duvall, they are the painter and they are Altman.

And most chilling of all, they are also us: gazing, always gazing.

No comments:

Post a Comment